The Australian Open is often framed as a battle against heat, hard courts, and early-season fitness. But beneath the surface, it presents a different and often underestimated challenge: circadian disruption.

For many players, Melbourne is the furthest stop on the calendar. Long-haul, eastward travel for most, compressed preparation windows, and unfamiliar match timings mean the Australian Open is less about shaking off rust and more about managing biology.

Professional Tennis Players Association on flights for professional players.

Source

Why Tennis Feels Jet Lag More Than Most Sports

Unlike some sports, tennis places a heavy demand on fine motor control, decision-making, reaction time and emotional regulation, all of which are tightly linked to circadian rhythms. There is no shared workload, no substitutions, and limited ability to hide on a bad day.

Add to that:

- Variable match times

- Short recovery windows between rounds

- High cognitive and emotional load

and jet lag becomes more than a travel inconvenience. It becomes a performance variable.

Kokkinakis and Murray did not leave Melbourne Park until almost 5am

Source

The Australian Open Circadian Problem

Most players arrive in Australia following significant transmeridian air travel, often from Europe and the Americas. Eastward travel is consistently harder to adapt to, requiring the body clock to advance, something it does reluctantly.

Early in the tournament, this misalignment often coincides with:

- Pre-season training blocks still bedding in.

- Limited exposure to local light-dark cycles.

- Match times that do not align with peak alertness.

The result is that players may be physically present but biologically out of sync.

How Long Jet Lag Symptoms Can Last

One of the most challenging aspects of jet lag is that symptoms do not resolve at the same pace. Sleep may improve after a few nights, while fatigue, mood, cognitive sharpness, and gut function can take longer to stabilise.

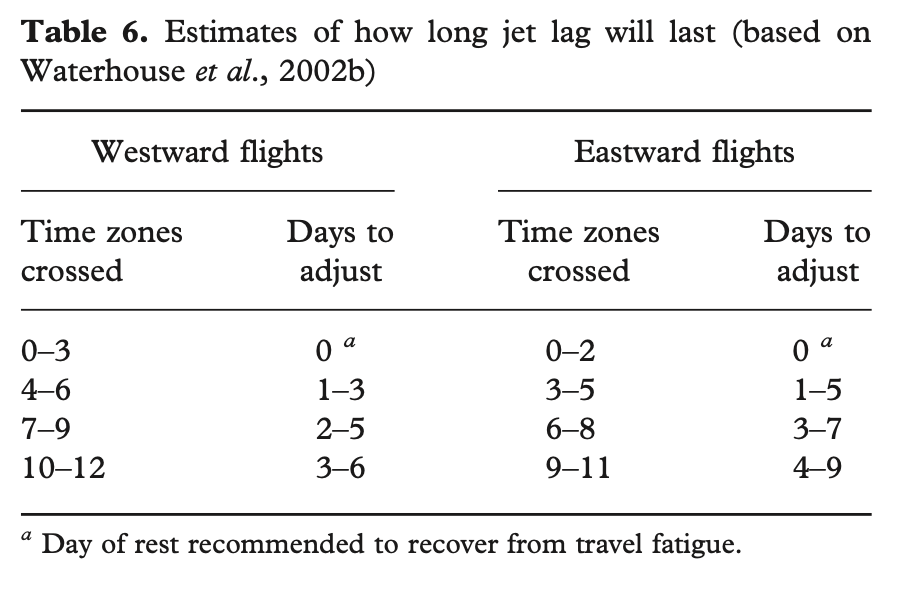

Peer-reviewed consensus papers suggest that the body clock can adjust at a rate of approximately one to two hours per day for each time zone crossed, with eastward travel generally requiring a longer adaptation period than westward travel (1;2). This means that a player travelling eight to ten time zones east may still be adapting well into the second week post-arrival.

Approximate days to adjust to a new time zone (6)

Source

Research and applied observations suggest the following symptom timelines are common:

- Poor sleep and daytime sleepiness

Often most pronounced in the first one to three days post-arrival, particularly when athletes are attempting to train or compete at local times that still fall within their biological night. - Excessive fatigue and reduced physical output

Can persist across the broader adaptation window. Athletes may complete sessions but report higher perceived effort and slower recovery between matches. Strength and other metrics of physical performance may be out of sync for several days! - Reduced mental performance

Circadian misalignment has been associated with impaired attention, slower decision-making, and reduced emotional regulation. In tennis, this can influence shot selection, error rates, and the ability to manage momentum shifts. - Irritability and mood disturbance

Mood changes are a recognised feature of jet lag and often present before athletes consciously identify sleep disruption as the underlying issue. - Gut symptoms and stool irregularity

The gastrointestinal system follows its own circadian rhythms. The dry plane cabin-air and abrupt changes in sleep and meal timing can disrupt gut motility, appetite, and stool regularity. For travelling athletes, this can add another layer of discomfort and unpredictability during competition.

From a performance perspective, this matters because symptoms can fluctuate rather than improve in a straight line. A player may feel sharp one day and flat the next without any clear reasoning.

Practical implications for coaches and performance staff

- In a study examining tennis serving accuracy, a mixed group of male and female players experienced up to a 31% reduction in accuracy after just one night of restricted sleep (five hours). While caffeine was shown to reduce the impact of this performance drop and can be a useful short-term aid when sleep is limited, it is not a viable long-term solution (5).

- As we spoke about previously here, remember those most important lifestyle body clock shifters: Light, exercise and food.

- Consider pre-adjusting light, exercise and food (in that order of priority) a few days before travel (something Phaze personalises based on a person’s profile and sleep data).

- Treat the first 48 hours post-arrival as a high-risk window for sleep disruption, fatigue and injury, even if the athlete subjectively feels fine. As such, plan low-intensity and low skill-demand training and practice sessions.

- Plan adaptation timelines that reflect the number of time zones crossed, with an additional buffer for eastward travel. You may also want to consider a delay strategy for large shifts eastwards (more than 8 time-zones) – again, this is something Phaze factors in.

- Expect gut symptoms to be part of the adaptation process, and stabilise meal timing, hydration, and food choices early.

What This Looks Like on Court

In practice, circadian disruption in Tennis is likely to show up as:

- Slow starts or inconsistent opening sets.

- Unforced errors at unusual moments.

- Emotional volatility under pressure.

- Matches extending longer than expected.

These are not fitness issues. They are timing issues.

Turning Jet Lag Into a Competitive Advantage

To a certain extent, jet lag itself is unavoidable at a tournament like the Australian Open. Poor adaptation is not.

The key shift for coaches and performance staff is to treat circadian alignment as a trainable and manageable factor, rather than something to simply endure. That includes:

- Pre-adjusting before travel.

- Strategic arrival timing.

- Prioritising light exposure alongside sleep.

- Adjusting training to accommodate circadian shifting.

- Interpreting match performance through a circadian lens.

At a tournament where margins are thin and conditions are demanding, these decisions matter most in the early rounds.

Why This Matters at the Australian Open

The Australian Open is not just the first Grand Slam of the year. It is one of the most demanding biological challenges on the sporting calendar.

Almost every player travels. All players deal with heat. But not every player adapts equally.

Those who understand and manage circadian load give themselves a quieter advantage, one that does not show up on a stat sheet but often shows up on the scoreboard.

Phaze helps athletes and performance teams plan circadian adaptation before and after long-haul travel, using personalised guidance on light exposure, sleep timing and training. At tournaments like the Australian Open, where margins are thin, better biological timing can be the difference in the early rounds.

References and Further Reading

- Arendt, J., 2009. Managing jet lag: Some of the problems and possible new solutions. Sleep medicine reviews, 13(4), pp.249-256

- Janse van Rensburg, D.C., Jansen van Rensburg, A., Fowler, P.M., Bender, A.M., Stevens, D., Sullivan, K.O., Fullagar, H.H., Alonso, J.M., Biggins, M., Claassen-Smithers, A. and Collins, R., (2021). Managing travel fatigue and jet lag in athletes: a review and consensus statement. Sports Medicine, 51(10), pp.2029-2050.

- Reilly, T., & Waterhouse, J. (2009). Sports performance: is there evidence that the body clock plays a role? European Journal of Applied Physiology.

- Samuels, C. (2012). Jet lag and travel fatigue: a comprehensive management plan for sport medicine physicians. Clinics in Sports Medicine.

- Reyner, L.A. and Horne, J.A., (2013). Sleep restriction and serving accuracy in performance tennis players, and effects of caffeine. Physiology & behavior, 120, pp.93-96.

- Voigt, R. M. et al. (2016). Circadian rhythm and the gut microbiome. International Review of Neurobiology.

- Waterhouse, J., Reilly, T. and Edwards, B., (2004). The stress of travel. Journal of sports sciences, 22(10), pp.946-966.

- Waterhouse, J., Reilly, T., & Edwards, B. (2007). Jet lag and air travel: implications for performance. Clinics in Sports Medicine.